A pocket watch found in time

Figure 1. Sandra Kerkvliet, Watch, Chain and Key, 2016.

‘One summer’s evening around dusk, we ventured out to look for wombats emerging from their burrows to graze. We stopped by the roadside. On the ground, we found an old watch, attached to a long chain. Had a wombat dropped them on the way to a tea party? Concerned they were someone’s precious family heirlooms, we handed in the watch and chain to the local police. Three months later, after no one stepped forward to claim the items, we became their proud new owners.’

And so in 1988, the watch (Figure 1) entered our family folklore. Discovered in a community founded on gold in the 1850s, we could not tell how long the watch had lain there. Despite exposure to the elements, the watch showed remarkably little damage, although it had received rough treatment previously; the glass lid does not close properly and while the hour and seconds hands are coppery, the minute hand is a different colour. We purchased a key to check whether the watch still functions – it does - but the watch’s cumbersome design now renders it more decorative than practical. We are yet to gain access to the watch’s inner workings. While the mechanism is most likely original, an assessment of the watch’s age is, for now, restricted to analysing its external features.

The watch, no doubt, was a significant acquisition for its first owner, perhaps a retirement ‘silver handshake’ or an inherited family heirloom. The watch may have been discarded once more practical designs became popular, but this analysis is mere guesswork. A date and initials etched inside the back lid may indicate an equally important milestone, but again this is speculation on our part.

While its past ownership is unclear, a study of horology is not required to determine the watch’s origins. The shape and size confirm it to be a ‘pocket watch’, so named in recognition of where it was placed. Evolving from the early ovoid‑shaped watches worn around the neck during the 1500s, pocket watches remained in vogue until the advent of wristwatches after World War I. Sometimes mistakenly referred to as ‘fob watches,’ smaller delicate open-face watches hanging from leather straps and worn by women, pocket watches were usually carried by men.

Figure 2. Sandra Kerkvliet, Hunter Watch Cover, 2016.

Figure 3. Kate Bousfield, My Father's Watch, 2016.

Figure 2 shows the lid of our pocket watch, known as a ‘Hunter’ or ‘Savonnette’ watch because of its hinged lid over the dial face. ‘Half- Hunter’ watches feature a similar lid with a glass panel insert. Figure 3 shows an ‘Open-face’ or ‘Lépine’ pocket watch. Open-face watches have no cover, instead using thick glass over the dial face. Family coats of arms sometimes appeared on Hunter watches, but our watch is unremarkable; it has a generic pattern common among other watches manufactured around the same period. The imperfection of the generic heraldic emblem on our Hunter watch indicates it was etched by hand.

The name of the British manufacturer, ‘Rotherhams’, appears on the dial face of the watch. In 1800, Britain’s watchmakers dominated the world’s watch production market, manufacturing 50% of the watches produced worldwide. By the 1900s, however, this percentage halved as other countries began using mass production techniques. In contrast, Britain remained largely reliant on skilled workmanship, handcrafting smaller numbers of high‑quality watches.

In 1747, Samuel Vale founded his clockmaking business in Coventry England. Forty-three years later, Richard Kevitt Rotherham, a past apprentice, became a partner in the business, later changing the company’s name to Rotherham and Sons. Despite continuing to handcraft watches, Rotherhams was an early adopter of machine-made production. By 1900, Rotherhams had diversified its operation to manufacture other products, safeguarding its future against a declining British watchmaking industry.

Before the 1824 Birmingham Assay Office Act legislated hallmarking of gold, silver items required hallmarking to establish authenticity, so a system of standardised assay marks was established. The hallmarks inside both lids of the Rotherhams watch confirm its quality and show the place and year of manufacture.

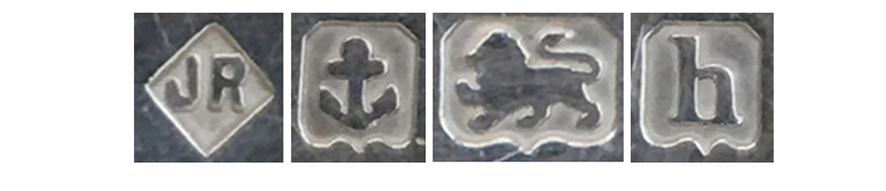

Figure 4. Sandra Kerkvliet, Pocket Watch Silver Marks, 2016.

Figure 4 shows the watch’s silver marks. The ‘JR’ diamond shape is Rotherhams’ ‘maker’s mark’, and the anchor ‘city mark’ confirms the watch was assayed in Birmingham. The lion ‘silver standard mark’ indicates a purity of 92.5% silver and 7.5% copper. The ‘h’ ‘date letter’ identifies that the watch was assayed in 1907. Used from 1748, ‘date letters’ were cycled in strings of 20 characters, changing their style in May each year.

Therefore, we can establish that the sterling silver watchcase was manufactured in 1907. Although less valuable than a watchcase of either gold or Brittania silver, a sterling silver watchcase was certainly more valuable than one of silver plate or bronze alloy. Consequently, although not likely to be the property of someone at the pinnacle of British society, the watch’s first owner would have been a gentleman of some means. As such, the watch had both societal and monetary value.

Another question now arises. Was the necklace-style chain found with the watch the original chain? The chain bears an Australian silver mark, and as British gentlemen of the era most commonly used ‘Albert chains’ to secure their pocket watches, it can be confirmed that the chain was added later. Coined after Queen Victoria’s consort Prince Albert, a single Albert chain featured a ‘T’ shape at one end threaded through a waistcoat buttonhole and a swivel hook at the other attached to a pocket watch.

It is unlikely that Rotherhams sourced Cornish silver to make the watch. Although Cornwall was Britain’s leader in mineral extraction, its silver sources had depleted several decades before the watch was made. Rotherhams may have sourced the silver, commonly a by-product of refining other metals such as lead, from as far away as Wales. Despite the distance, Rotherhams artisans would have found the silver easy to work with once it arrived. Malleable at room temperature, silver is easier to handle than gold, which requires heating to be shaped.

In its heyday, the watch’s solid construction implied reliability and added prestige to its wearer in a period when only well-to-do members of society carried their own timepieces. Further, the watch offered its first owner a means of instantly telling the time regardless of location, something not afforded society’s less affluent members who remained reliant on their close proximity to building and mantle clocks.

While we do not know how the watch came to be by the roadside or who first felt the watch’s comforting weight in their hand, we can revel in its mystery. For now at least, the watch is tucked away safely for our descendants. We can only hope that the watch is never lost again.

Figure 5. Amanda Bousfield, Poppa's Watch, March 2016.

Credits and References

Assay Office Birmingham. ‘Assay Office Birmingham – Statutory History’. Accessed 7 August 2016. https://theassayoffice.co.uk/assay-office-birmingham/assay-office-Birmingham-statutory-history.

Assay Office Birmingham. ‘The Home of UK Hallmarking’. Accessed 7 August 2016. https://theassayoffice.co.uk/.

Boettcher, David. ‘About Watchcases and Crowns’. Last modified July 2016. http://www.vintagewatchstraps.com/watchcases.php.

Carter’s Price Guide to Antiques. ‘Albert Chains’. Accessed 7 August 2016. http://www.carters.com.au/index.cfm/index/1490-albert-chains/.

Chain. Sterling Silver, Private Collection.

Coventry Watch Museum Project. ‘The History of Coventry Watchmaking: Origins of the Trade’. Accessed 7 August 2016. http://www.coventrywatchmuseum.co.uk/history.asp.

eBay. ‘Your Guide to Buying an Antique Engraved Pocket Watch’. Last modified 15 March 2016. http://www.ebay.com.au/gds/Your-Guide-to-Buying-an-Antique-Engraved-Pocket-Watch-/10000000177317448/g.html.

Grace’s Guide to British Industrial History. ‘Rotherham and Sons’. Accessed 7 August 2016. http://www.gracesguide.co.uk/Rotherham_and_Sons.

Great British Watch Company. ‘British Watchmaking’. Last modified 3 July 2016. http://great-british-watch.co.uk/british-watchmaking/.

Kerkvliet, Sandra. A Pocket Watch in Time. Unpublished manuscript, 2016.

Korda, Michael. ‘Marking Time: Collecting Watches and Thinking about Time’. New York: Barnes & Noble Publishing Inc., 2004, p. 75. Accessed 7 August 2016. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=9VYKILqUThQC&pg=PA75&lpg=PA75&dq=were+pocket+watches+engraved+with+coat+of+arms&source=bl&ots=JEM0hzmoB5&sig=I_8B14d43rM7EWrb2R1BbQKG3Rk&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjJl4jw1K7OAhVEGZQKHaQND2Y4ChDoAQggMAE#v=onepage&q=were%20pocket%20watches%20engraved%20with%20coat%20of%20arms&f=false.

Macquarie Encyclopedic Dictionary. ‘horology’. Macquarie Encyclopedic Dictionary: The Signature Edition. Sydney: Australia’s Heritage Publishing Pty Ltd, 2010, p. 599.

Mineral Statistics of the U.K. ‘Cornish Mineral Production’. Last modified 30 July 1996. http://projects.exeter.ac.uk/mhn/MS/co-intro.html.

Muttitt, Louise Mary. ‘Why use silver for jewellery making?’ in Making Silver Jewellery. Marlborough, United Kingdom: The Crowood Press Ltd, 2014. ePUB e-book.

Online Encyclopedia of Silver Marks, Hallmarks & Makers’ Marks. ‘British Hallmarks’. Accessed 7 August 2016. http://www.925-1000.com/british_marks.html.

Online Encyclopedia of Silver Marks, Hallmarks & Makers’ Marks. ‘Guide to World Hallmarks’. Accessed 7 August 2016. http://www.925-1000.com/foreign_marks.html.

Pocket Watch. ‘Pocket Watch Types’. Accessed 7 August 2016. https://www.pocketwatch.co.uk/.

Pocket watch key. Private Collection.

Rotherham and Sons. Pocket watch, 1907. Sterling silver, 7cm. x 5cm., 100g. Private Collection.

Silver Makers’ Marks. ‘Birmingham Assay Office (J)’. Accessed 7 August 2016. http://www.silvermakersmarks.co.uk/Makers/Birmingham-JN-JS.html#JR.

Silver Makers Marks. ‘Birmingham Date Letters’, 1907. Accessed 7 August 2016. http://www.silvermakersmarks.co.uk/Dates/Birmingham.html.

St Andrews Primary School Council. St Andrews, A Village Built on Gold. St Andrews Primary School Council, 1998, p. 10.

Wikipedia. ‘Metal mining in Wales’. Last modified 23 February 2016. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metal_mining_in_Wales.

Wikipedia. ‘Pocket watch’. Last modified 10 June 2016. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pocket_watch.

Wikipedia. ‘Silver’. Last modified 7 August 2016. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silver.